THE MOVIE STUDIO IN OUR BACKYARD

by Scott MacGillivray

Norman Kay, a former chairman of the Boston Brats, told a story

that there was once a movie studio near our meeting place in

Newton, Massachusetts. Norman was working in a camera shop in

1950, and a customer mentioned the studio. Norman said that his

mother had appeared as an extra in one of the films. The

customer, a former movie director, replied, “Tell your mother

she may have appeared in a picture with Stan Laurel.” It’s

possible—Stan was touring America in vaudeville during the late

1910s, and he may well have found time to make a little extra

money in Newton.

The Atlas Studio was just down the road from our meeting hall. It was on Carver Road, off Woodward Street (some of us travel on Woodward to get to our meetings). Leon Dadmun (1861–1943), a newspaperman who also wrote and directed local stage plays, bought a professional movie camera and began photographing local events. He was no cub cameraman; he was in his early fifties when he became interested in then-new motion picture photography. One of his films received national attention in June 1914: a newsreel of a disastrous fire that swept through Salem, Massachusetts and caused $12 million in damage, or $368 million today. Dadmun’s fine work brought him in contact with professional movie men, and he was inspired to form his own company. The Dadmun Film Company made industrial and commercial films until 1917, when it merged with Boston’s Atlas Film Corporation; Atlas had recently built a studio in Newton Highlands. In May 1917, 65 stockholders voted 56-year-old Dadmun in as president of Atlas Film Corporation. Production of theatrical films began on May 18, featuring beauty contest winner Beatrice Roberts.

The Atlas grounds encompassed 25 acres (with only one entrance!). The studio was a stone structure built at a cost of $30,000 ($732,000 today). Moving Picture World described the physical plant: “This new studio is located in one of the most scenically beautiful spots of Massachusetts. The glass roof is pitched at such an angle that it affords the best possible light, and the studio is wired for the latest electric lighting effects. The studio is also in easy motoring distance of good locations for scenic requirements of any script, as Massachusetts is justly famous for its natural scenery. The first floor of the studio is devoted to one monster stage which will easily accommodate three or four companies at the same time. On the floor directly beneath the stage is located the laboratory, film rooms, assembling rooms, prop and dressing rooms.”

In those

days of fly-by-night moviemakers, who made quickie films

outdoors with one portable camera and very little money, it

seems incredible that there was a permanent, fully equipped

movie studio trying to make a go of it in Massachusetts. Local

stage actors worked at the Atlas studio in the mornings, before

their theater calls. Atlas’s first star was 12-year-old Leland

Benham of Boston, already a six-year screen veteran. He starred

in the “Peck’s Bad Boy” series for Atlas, beginning in October

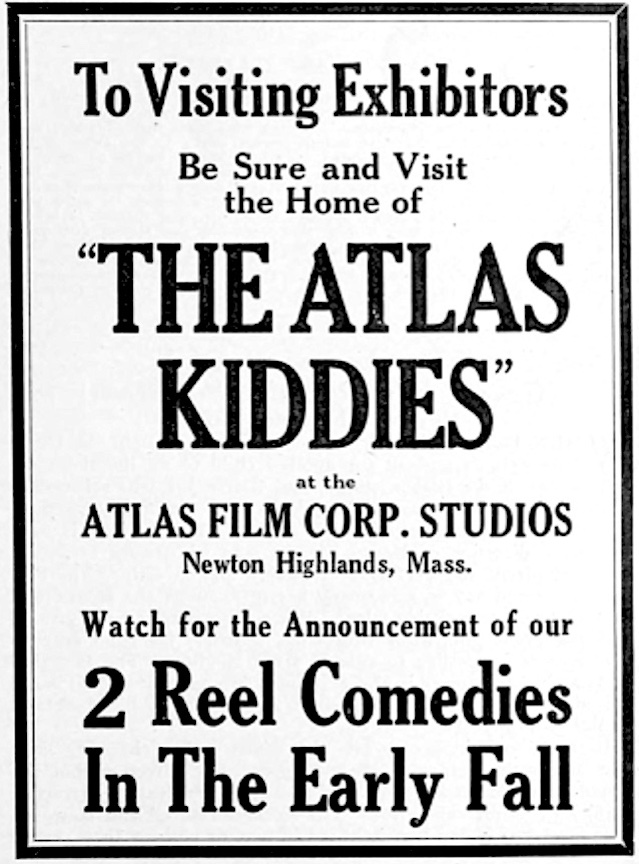

1917. In 1918 the studio launched a new two-reel-comedy series,

“The Atlas Kiddies,” four years before Hal Roach launched the

“Our Gang” series.

The Place of Honeymoons, a five-reel feature, was filmed by Atlas in 1920 with future prominent player Montagu Love. Pioneer Film Corporation of Illinois released it but withheld payments to Atlas. Many small theaters had already closed due to the 1918–20 flu pandemic, and many small distributors were in financial trouble. These market forces evidently broke the Newton studio. Atlas finally took Pioneer to the Supreme Court in March 1922, citing a broken contract and “an attempt to cheat and defraud the plaintiff out of its just share of the profits.” Justice Irving Lehman denied the petition in April, on the grounds that Pioneer was then bankrupt and in receivership.

Motion Picture News reported in 1923 that the Atlas studio, “built several years ago for a company that thrived for awhile and then went under, has recently been the scene of great activity again.” Although Leon Dadmun was listed in corporate papers as the company’s treasurer, he was still at the helm, doing business as Pictures-in-Motion, Inc. That year Dadmun produced the “Just Folks” series, two-reel subjects based on the poems of Edgar Guest. Dora was taken from the Alfred, Lord Tennyson poem. Gossip was based on “And a Little Child.” The Soul Call, a drama filmed in the fall of 1922, replicated a village on the Russia-Germany border in the then-pastoral Newton countryside, and used Newton neighbors as extras. Dadmun held the first public showing in Newton Highlands so the locals could see themselves on the screen. The star was Edward Earle, later a familiar character player (he’s in five Laurel & Hardy features).

Leon Dadmun had a brush with greatness in 1924, when premier director D. W. Griffith used the Atlas premises for some of the location scenes in his epic feature film America. The famous Pathé company had also contracted with Dadmun. These prestigious and profitable arrangements must have had an effect on Leon Dadmun’s priorities. He gave up the idea of producing his own theatrical films in favor of turning Atlas into a rental facility, making his equipment and studio space available for commercial use. Various manufacturers and merchants produced special advertising films at the Atlas studio. Dadmun did direct one feature film for producer Paul Whitcomb in 1924, The Pearl of Orr’s Island (filmed in Massachusetts and released in 1925 as The Pearl of Love).

In 1926 The Boston Globe asked its readers, “Want to break into the movies? Long hours, no Sundays or holidays off, no pay, some expense to yourself—and a chance to make good. Like to try it? Then make yourself acquainted with the Little Screen Players.” This was an organization of former stage or screen personnel and amateur talent, joining forces to make their own movies in the Boston area on Sundays. As the Globe reported, “You don’t even have to join the organization. For $1.25, the actual cost of the film [$21.42 today], you can have a screen test, 10 feet of film.” The applicant would receive a film clip running only 10 seconds, but the actor would have a motion picture to present instead of the usual still photograph. One of the Little Screen Players was 18-year-old Harriet Krauth of Medford, discovered by Paramount and groomed for stardom (as Jeanne Morgan) alongside fellow Massachusetts native Thelma Todd. Harriet soon changed her professional name to Jean Fenwick and worked in pictures into the 1950s. Her sister became a star as Marian Marsh.

The Little Screen Players had filmed outdoor scenes for a comedy called Hold On a Minute, but needed interior scenes to finish it. Only then did they wonder if there was a studio anywhere in Greater Boston. Somebody remembered Atlas, “hidden in the woods between Newton Highlands and Waban,” and the studio could be hired for a flat $100 a day ($1,771 today). The humble amateurs scraped up the cash, showed up at 8:00 on a Sunday morning, and worked all day, shooting 19 scenes on 19 sets until 2:30 Monday morning, and Leon Dadmun collected his $100. The Little Screen Players became Dadmun’s stock company, and he used them in his advertising films.

In 1927 a Boston Globe reporter took a dare to make a screen test, which was then a popular craze. He thought of his old friend Leon Dadmun in Waban, who told him: “When I make a screen test, it’s a business matter. Foolish people who have no intention of going into motion pictures sometimes offer me money for tests, but I always refuse. This fad of having screen tests for the fun of it is not to my liking. And besides, I have all the legitimate work I can attend to.” This last remark is suggestive: by “legitimate work” he may have meant the legitimate stage. Dadmun had other interests by the late 1920s (he was then at retirement age) and the Atlas studio was now only a sideline. Indeed, Dadmun had sold off much of his land in October 1925, so he no longer needed a steady income.

There is no evidence that Dadmun retooled his studio for the new talking-picture technology. That took Atlas out of the running as a viable production facility. In 1932 he still used the studio laboratory as his workshop, where he experimented with 3-D movie photography. A fire destroyed the interior of the studio on or about July 8, 1933. The cause was not reported, but nitrate film was highly flammable and may have been a factor. The structure didn’t burn to the ground because it was a stone building. Damage amounted to $18,000 ($421,000 today), including much scenery, and Dadmun declined to rebuild.

After the fire, Dadmun worked as a photographer and actor. Apart from a 1936 trade report that Dadmun was “taking over the Atlas Film Company,” there was no further word in movie circles about Atlas. Leon Dadmun remained active in local productions, including tours of army camps, until his death on September 20, 1943 at age 82, at his Newton Highlands home—one mile from his Atlas studio. His obituary makes no mention of his years as a movie producer, so Atlas wasn’t remembered even then. The studio no longer exists; the building was razed by developers, and Carver Road has been residential for decades.

If Atlas’s silent-era productions still exist, I don’t know of any. Many silent films were destroyed after their theatrical runs, so producers could reclaim the silver in the film stock. Here’s a likely reason why there are no Atlas Studios pictures today: Leon Dadmun appears to have sold his productions outright to independent distributors. Let’s say Dadmun makes a film for $2,500 and sells it to someone else for $5,000. He doubles his cash investment immediately, and doesn’t have to bother with paying labs for prints, or spending money for promotion, or sending the films around to theaters, or storing the reels when they come back. He just keeps the cash and moves on to his next project. For example, his 1923 feature Gossip was copyrighted by its owner of record, Truart Film Corporation. Truart made 462 prints—that’s 2,310 reels of film—at no cost to Dadmun. This might explain why there are no Atlas listings in trade journals, and why Dadmun left none of his productions behind.

There was another Atlas studio in San Francisco (Atlas Educational Film Company, formed in 1915), making instructional films for schools and libraries, and then relocating to Chicago in March 1924 to make theatrical films. Any surviving antique film with the Atlas brand name is probably a product of Atlas Educational, not Atlas of Newton.

The little studio in Newton is now an obscure footnote in the history of silent films—with no known exhibits to mark its very existence—but the Boston Brats can salute this faint footprint of silent movies in our little corner of New England.

Copyright © 2024 by Scott MacGillivray.